Publikohen të dhënat e deklarimit pasuror për funksionar të lartë të emëruar Anëtar të Kolegjit të Posaçëm të Apelimit KPA

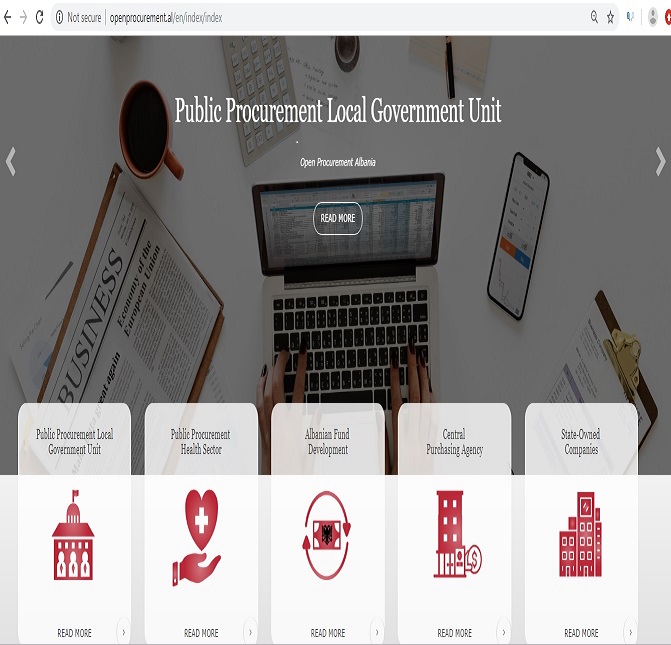

Në portalin Spending Data Albania rubrika Para dhe Pushtet janë publikuar të mirë kategorizuara, të dhënat e deklarimit pasuror për funksionar të lartë të emëruar Anëtar të Kolegjit të Posaçëm të Apelimit KPA. Të dhënat janë aksesuar sipas të drejtës për informim përmes dokumentit të vetë deklarimit pranë Inspektoratit të Lartë të Deklarimit të Pasurive dhe Kontrollit të Konfliktit të Interesit. Informacioni përveç tabelës së detajuar nga data analist të programit tonë, shoqërohet edhe me dokumentin PDF kopje e origjinalit për ti dhënë mundësi publikut për mirë informim. Informacioni i marrë nga dokumente të vetë deklarimit Fillestare apo Vjetore, përmban të dhëna për asete pasurore të patundshme apo pasuri të tjera, kontrata sipërmarrje, porosie apo investimi, të dhëna mbi shpenzime vjetore, të dhëna mbi likuiditet, debi, kredi apo tituj pronësie, asete të bizneseve dhe të drejta pasurore të fituara përmes formave të ndryshme. Përveç subjektit funksionar i lartë i emëruar, të dhënat e vetë deklarimit kanë informacion edhe për pjesëtarë të ngushtë të rrethit familjarë të lidhur në interesa ekonomik me funksionarin e lartë të emëruar. Deklarimet pasurore për funksionar të KPK i gjeni sipas Link si vijon.

1. Albana SHTYLLA http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/282

2. Ardian HAJDARI http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/1090

3. Ina RAMA http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/383

4. Luan DACI http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/1091

5. Natasha MULAJ http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/1092

6. Rezarta SCHUETZ (GABA) http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/1093

7. Sokol COMO http://spending.data.al/sq/moneypower/view/id/100

Të dhëna për jetëshkrimin, eksperiencën profesionale dhe akademike, kualifikime të veçanta, dokumenta që lidhen me profilin në shkenca juridike dhe integritetin në detyrë për secilin anëtar të KPK ju mund ti gjeni në faqen e re të ndërtuar nga AIS Akses Info Drejtësi kliko këtu

Të dhëna për institucionin KPA akte, vendime, njoftime zyrtare etj janë në ndërfaqen e krijuar po tek Akses Info Drejtësi link.